WORKING GROUP DRAFT – IN CONFIDENCEReport on Government Services 2026

PART E, SECTION 13: RELEASED ON 5 FEBRUARY 2026

13 Services for mental health

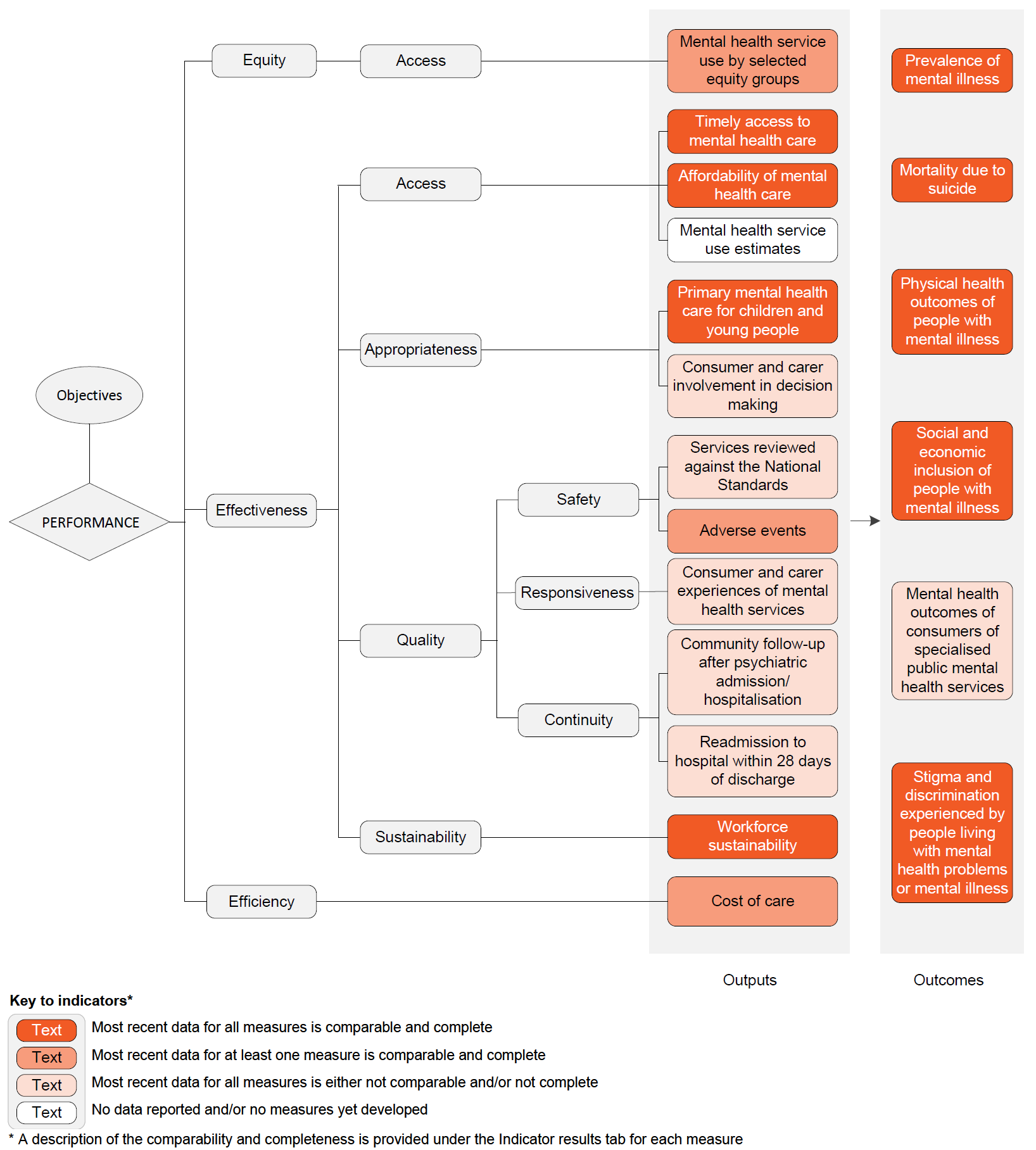

This section reports on the Australian, state and territory governments’ management of mental health and mental illnesses. Performance reporting focuses on state and territory governments’ specialised mental health services, and services for mental health subsidised under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (Medicare) (provided by General Practitioners (GPs), psychiatrists, psychologists and other allied health professionals).

Content warning

If you are experiencing crisis, feel worried about harming yourself or think someone may be in danger, please seek help.

If life is in imminent danger please call 000.

The Indicator results tab uses data from the data tables to provide information on the performance for each indicator in the Indicator framework. The same data is also available in CSV format.

Data downloads

![]() 13 Services for mental health data tables (XLSX 727.0 KB)

13 Services for mental health data tables (XLSX 727.0 KB)

![]() 13 Services for mental health dataset (CSV 2.4 MB)

13 Services for mental health dataset (CSV 2.4 MB)

Refer to the corresponding table number in the data tables for detailed definitions, caveats, footnotes and data source(s).

Objectives for services for mental health

Services for mental health aim to:

- promote mental health and wellbeing, and where possible prevent the development of mental health problems, mental illness and suicide, and

- when mental health problems and illness do occur, reduce the impact (including the effects of stigma and discrimination), promote recovery and physical health and encourage meaningful participation in society, by providing services that:

- are high quality, safe and responsive to consumer and carer goals

- facilitate early detection of mental health issues and mental illness, followed by appropriate intervention

- are coordinated and provide continuity of care

- are timely, affordable and readily available to those who need them

- are sustainable.

Governments aim for services for mental health to meet these objectives in an equitable and efficient manner.

Mental health relates to an individual’s ability to negotiate the daily challenges and social interactions of life without experiencing undue emotional or behavioural incapacity (DHAC 1999). The World Health Organization describes positive mental health as:

… a state of wellbeing in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community (WHO 2001).

Mental illness is a term that describes a diverse range of behavioural and psychological conditions. These conditions can affect an individual’s mental health, functioning and quality of life. Each mental illness is unique in its incidence across the lifespan, causal factors and treatments.

There are a range of services provided or funded by Australian, state and territory governments that are specifically designed to meet the needs of people with mental health issues. The key services are:

- Medicare‑subsidised mental health specific services that are partially or fully funded under Medicare on a fee‑for‑service basis and are provided by GPs, psychiatrists, psychologists or other allied health professionals under specific mental health items.

- State and territory government specialised mental health services (treating mostly low prevalence, but severe, mental illnesses), which include:

- Admitted patient care in public hospitals – specialised services provided to inpatients in standalone psychiatric hospitals or psychiatric units in general acute hospitals. While not a state and territory government specialised mental health service, this section also reports on emergency department presentations for mental health related care needs (where data is available). (Data on emergency department presentations for mental health related care needs is reported where available in table 13A.18.)

- Community‑based public mental health services, comprising:

- ambulatory care services and other services dedicated to assessment, treatment, rehabilitation and care, and

- residential services that provide beds in the community, staffed onsite by mental health professionals.

- Not for profit, non‑government organisation (NGO) services, funded by the Australian, state and territory governments focused on providing wellbeing, support and assistance to people who live with a mental illness. These include crisis, support and information services such as Beyond Blue, Lifeline, Kids Helpline, and ReachOut.

- The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), which began full roll out in July 2016. People with a psychiatric disability who have significant and permanent functional impairment are eligible to access funding through the NDIS. In addition, people with a disability other than a psychiatric disability, may also be eligible for funding for mental healthrelated services and support if required.

- The Australian, state and territory governments also share a focus on prevention and early intervention through suicide prevention programs and investment to reduce gaps in care (including emphasising a whole of system approach and the role of social determinants of health on people’s mental health and wellbeing).

There are also other services (for example, specialist homelessness services) provided and/or funded by governments that make a significant contribution to the mental health treatment of people with mental illness but are not specialised or specific mental health services. Information on these services can be found on the Mental Health section of the Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) website (2024a).

State and territory governments are responsible for funding, delivering and/or managing specialised services for mental health including inpatient/admitted care in hospitals, community‑based ambulatory care and community‑based residential care.

The Australian Government is responsible for overseeing and funding of a range of services for mental health and programs that are primarily provided or delivered by private practitioners or NGOs. These services and programs include Medicare‑subsidised services provided by GPs (under both general and specific mental health items), private psychiatrists and other allied mental health professionals, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) funded mental health‑related medications and other programs designed to prevent suicide or increase the level of social support and community‑based care for people with a mental illness and their carers. The Australian Government also funds state and territory governments for health services, most recently through the approaches specified in the National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement and the National Health Reform Agreement (NHRA) which includes a mental health component.

A number of national initiatives and nationally agreed strategies and plans underpin the delivery and monitoring of services for mental health in Australia including:

- the Mental Health Statement of Rights and Responsibilities (Standing Council on Health 2012)

- the National Mental Health Policy 2008 (DoH 2009)

- National Mental Health Plans, the most recent being the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan 2017–2022 (COAG 2017)

- the National Mental Health Workforce Strategy 2022–2032 (DoHAC 2023).

Under the National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement 1, the Australian, state and territory governments are jointly responsible for a number of areas including:

- mental health workforce planning, training and accreditation

- mental health promotion, prevention, early intervention and social and emotional wellbeing programs, suicide prevention, stigma reduction

- help and crisis hotlines

- psychosocial support services for people who are not supported through the NDIS

- contributions to the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (reducing suicide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people towards zero, ensuring all services funded by Australian governments are culturally safe and responsive, and building a strong, sustainable community‑controlled sector).

- National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement, 2022

https://federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/sites/federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/files/2022-03/nmh_suicide_prevention_agreement.pdf Locate Footnote 1 above

https://federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/sites/federalfinancialrelations.gov.au/files/2022-03/nmh_suicide_prevention_agreement.pdf Locate Footnote 1 above

Nationally in 2022‑23, around $12.6 billion in real government recurrent expenditure was allocated to services for mental health, equivalent to $478.47 per person in the population (table 13A.1 and figure 13.1). State and territory governments made the largest contribution ($8.0 billion or 63.5%, which includes Australian Government funding under the NHRA), with Australian Government expenditure of $4.6 billion (table 13A.1).

Expenditure on Medicare‑subsidised services was the largest component of Australian Government expenditure on services for mental health in 2022-23 ($1.5 billion or 33.7%) (table 13A.2). This comprised Medicare‑payments for psychologists and other allied health professionals (17.7%), consultant psychiatrists (9.3%) and GP services (6.7%) (table 13A.2). The Australian Government also spent $659.0 million in 2022‑23 on mental health related medications under the PBS (table 13A.2).

Nationally, in 2022-23, expenditure on admitted patient services was the largest component of state and territory governments’ expenditure on specialised mental health services ($3.3 billion or 41.4%), followed by expenditure on community‑based ambulatory services ($3.2 billion or 39.0%) (table 13A.3). State and territory governments’ expenditure on specialised mental health services, by source of funds and depreciation (which is excluded from reporting) are in tables 13A.4 and 13A.5 respectively.

In 2023-24, 10.6% of the total population received Medicare/DVA services, with 1.9% of the total population receiving state and territory government specialised mental health services in 2022‑23 (the most recent data available) (figure 13.2). While the proportion of the population using state and territory government specialised mental health services has remained relatively constant, the proportion using Medicare/DVA services has increased steadily over time from 9.0% in 2014‑15 to 10.6% in 2023‑24. Service use per person increased for all service types across the time series, however GPs remain the most commonly accessed service provider (table 13A.7).

Information on the proportion of new consumers who accessed state and territory governments’ specialised and Medicare-subsidised services for mental health are available in tables 13A.8–9.

For the first time, the 2021 Census collected information on diagnosed long‑term health conditions. Over two million people reported having a diagnosed long‑term mental health condition (2,231,543) (ABS 2022).

Medicare‑subsidised services for mental health

In 2023‑24, 12.6 million Medicare‑subsidised services for mental health were provided by psychologists (clinical and other services) (6.0 million), psychiatrists (2.8 million) and other allied health professionals (0.5 million). GPs provided a further 3.3 million Medicare‑subsidised specific services for mental health. Service usage rates varied across states and territories (table 13A.10).

GPs are often the first service accessed by people seeking help when suffering from a mental illness (AIHW 2024b). They can diagnose, manage and treat mental illnesses and refer patients to more specialised service providers. According to a 2023 report by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners, mental health issues were the single most common reason patients visited their GP for the seventh year in a row (RACGP 2023).

State and territory governments’ specialised mental health services

Across states and territories, the mix of admitted patient and community‑based services and care types differ. As the unit of activity varies across these three service types, service mix differences can be partly understood by considering items which have comparable measurement such as expenditure (table 13A.3), numbers of full time equivalent (FTE) direct care staff (table 13A.11), accrued mental health patient days (table 13A.12) and mental health beds (table 13A.13).

Additional data is also available on the most common principal diagnosis for admitted patients, community‑based ambulatory contacts by age group and specialised mental health care by Indigenous status on the Mental Health section of the AIHW website (2025).

Crisis and support organisations

Crisis, support and information services such as Beyond Blue, Lifeline and Kids Helpline are provided to support Australians experiencing mental health issues. In 2022-23:

- Lifeline received 1,091,424 calls and answered 867,048 calls.

- Kids Helpline received 273,204 answerable contact attempts (call, webchat and email) with 117,720 contacts answered.

- Beyond Blue received 276,212 contacts and responded to 207,272 contacts (unpublished AIHW).

National Disability Insurance Scheme

The NDIS provides support to people with a significant and enduring primary psychosocial disability. At June 30, 2024, there were 63,837 active NDIS participants with a psychosocial disability (9.7% of all participants) (NDIA 2024), receiving approximately $5.3 billion in payments (table 13A.14).

Errata

Note: An errata was released for section 13 Services for mental health above on 6 February 2025. The following changes have been made to section 13:

- Data table 13A.21, footnote (l) and Data table 13A.58, footnote (h) have been updated to refer to the 2021 Census.

A PDF of Part E Health can be downloaded from the Part E sector overview page.